Nurarihyon

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (May 2016) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Nurarihyon (滑瓢[1] or ぬらりひょん) is a Japanese yōkai.

Concept

Generally, like the hyōtannamazu, they are considered a monster that cannot be caught.[1] One can find that it often appears in the yōkai emaki of the Edo Period, but any further details about it are unknown. In folktale legends, they are a member of the Hyakki Yagyō (in the Akita Prefecture), and there is a type of umibōzu (in the Okayama prefecture that can be found under that name, but it is not clear whether they came before or after the "nurarihyon" in the pictures.[2][3]

It has been thought that they are a "supreme commander of yōkai," but this has been determined to be simply a misinformed or common saying, as detailed in a later section

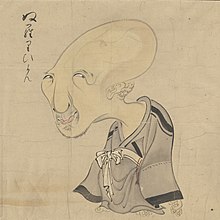

In yōkai pictures

In the Edo Period Japanese dictionary, the Rigen Shūran, there is only the explanation "monster painting by Kohōgen Motonobu."[4] Also the Kiyū Shōran (嬉遊笑覧) quotes the Bakemono E (化物絵) drawn by Kohōgen, where among the yōkai, one by the name of "nurarihyon" can be seen,[5] and it is also depicted in the Hyakkai Zukan (1737, Sawaki Suushi) and the Hyakki Yagyō Emaki (1832, Oda Gōchō, in the Matsui Library), among many other emakimono. It is a bald old person with a distinctinve shape, and depicted wearing either a kimino or a kasaya. Without any explanatory text, it is unclear what kind of yōkai they were intending to depict.

The Kōshoku Haidokusan (好色敗毒散), a ukiyo-zōshi published in the Edo Period gives the example, "its form was nurarihyon, like a catfish without eyes or mouth, the very spirit of lies," so it is known that it is word used with a meaning similar to noppera-bō but as an adjective.[3]

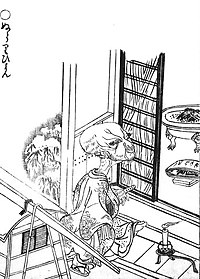

The Gazu Hyakki Yagyō by Toriyama Sekien depicts a nurarihyon hanging down from a kago. Like the emakimono, this one has no explanatory text, so not many details are known, but the act of disembarking from a vehicle was called "nurarin," so it is thought that nurarihyon was a name given to a depiction of this.[3] Furthermore, it is also theorized that this depicts the libertines who go to the red light district.[6] Natsuhiko Kyōgoku and Katsumi Tada posit that "nurari" is an onomatopoeic word meaning the state of slipperiness, and "hyon" similarly means a strange or unexpected circumstances, which is why "nurarihyon" was the name given to a yōkai that was slippery (nurarikurari) because it cannot be caught.[6] In the Gazu Hyakkai Yagyō, its name is written as "nūrihyon" but considering the all the literature and emakimono before it, it is generally thought that this is simply a mistake.[4]

From its appearance, it is also theorized that this yōkai was born because an old person was mistaken for a yōkai.

Legends

Okayama Prefecture

According to Hirakawa Rinboku, in the legends of Okayama Prefecture, the nurarihyon is considered similar to umi-bōzu,[7][2] and they are a round yōkai about as big as a human head that would float in the Seto Inland Sea, and when someone tries to catch it, it would sink and float back up over and over to taunt people.[6] It is thought that they would go "nurari" (an onomatopoeia) and slip from the hands, and float back up with a "hyon" (an onomatopoeia), which is why they were given this name.[3]

Presently, it is thought that these are portuguese man o' war, spotted jelly, and other large squid[6] and octopi that have been seen as yōkai,[3] so it is thought that this is a different thing from the aforemnetioned nurarihyon that takes on the shape of an old person.[8]

Akita Prefecture

In Yuki no Dewaji (雪の出羽路) (1814) in the Sugae Masumi Yūranki by the Edo Period traveler Sugae Masumi, there is the following passage:

If you pass by the Sae no Kamizaka at evening among other times in a leisurely stroll with a light drizzle and thick clouds, there would be a man who meets with a woman, the woman would meet with the man, and nurarihyon, otoroshi, nozuchi, among others would go on a hyakki yagyō, so some call it the bakemonozaka (monster hill).[9]

In the same book is written that the "Sae no Kamizaka" (道祖ノ神坂) is in the town of Sakuraguchi, Inaniwa, Ogachi District Dewa Province (now the town of Inaniwa, Yuzawa, Akita Prefecture).[10]

Modern nurarihyon

In yōkai-related literature, children's books, and illustrated references from the Shōwa, Heisei, and beyond, the "nurarihyon" would enter people's homes in the evening when the people there are busy and then drink tea and smoke like it's their own home. It is explained that when people see this person, they would think "this person is the owner of the house," so they couldn't try to chase it away, or not even notice. It is also explained that they are a "supreme commander of yōkai."[11]

However, folk legends that contain these characteristics cannot be found in any examples or references, so the yōkai researchers, Kenji Murakami and Katsumi Tada posit that the idea that they come into houses comes from the following passage in the Yōkai Gadan Zenshū Nihonhen Jō (妖怪画談全集 日本篇 上, "Discussion on Yōkai Pictures, Japan Volume, First Half") by Morihiko Fujisawa, which was written below Toriyama Sekien's illustration of the nurarihyon in that book:

While it is night is still approaching, the nurarihyon comes to visit as the chief monster.[12]

Those two yōkai researchers posit that this caption resulted in the proliferation of the idea in later years, and that it was actually an originally idea that came as an interpretation of Toriyama Sekien's picture.[6][2] Murakami and Tada posit that in fact, Fujisawa's assertion that the "nurarihyon comes to visit as the chief monster" is nothing more than a big interpretation.[6][2]

Also, in Wakayama Prefecture, stories where a nurarihyon appear were published as explanations,[13] but this story originally came from a story titled "Nurarihyon" in the collection of writings, "Obake Bunko 2, Nurarihyon" (Library of Monsters 2: Nurarihyon) by Norio Yamada, so it is posited that this is also an original creation.[6]

Toward the end of the Shōwa period, on the basis of Fujisawa's interpretation in that caption, the explanation that they "come into one's home" or that they are a "supreme commander of yōkai" took a life of its own after Mizuki Shigeru and Arifumi Satō spread them through their own illustrated yōkai reference books,[3] and in the animated television series, the 3rd "GeGeGe no Kitarō" (starting in 1985), a nurarihyon was the antagonist and arch-enemy of the main character Kitarō and was a self-proclaimed "supreme commander," which altogether can be seen as things that made their perception as being "supreme commanders" even more famous.[14]

The literary scholar Kunihiro Shimura states that all these above characteristics have made the legend stray far from its original meaning and has become artifically distorted.[2] On the other hand, Natsuhiko Kyōgoku states that in his opinion, this yōkai is performing its function just well in its present form so there is no problem,[15] and that by understanding yōkai as a living culture, he does not mind that they change to fit with the times.[16] Natsuhiko Kyōgoku participated in the animated television series, the 4th "Gegege no Kitarō" as a guest writer for the 101st episode, but here, the nurarihyon would be in its original form, as an octopus.

They are also depicted as in Hell Teacher Nūbē as a ruined visitor god.

Etymology

The name Nurarihyon is a portmanteau of the words "Nurari" (Japanese: ぬらり or 滑) meaning "to slip away" and "hyon" (Japanese: ひょん or 瓢), an onomatopoeia used to describe something floating upwards. In the name, the sound "hyon" is represented by the character for "gourd".[17] The Nurarihyon is unrelated to another, similarly named ocean Yōkai from Okayama Prefecture.[18]

Appearance and behaviour

The Nurarihyon is usually depicted as an old man with a gourd-shaped head and wearing a kesa.[17] In some depictions he also carries a single sword rather than the standard two to demonstrate his wealth. There is speculation that in Toriyama Sekien’s portrayal of Nurarihyon, he serves as a political cartoon to represent the aristocracy. [19] Others suggest that he is retired from a samurai family due to the sword and his clothing style.[20]

The Nurarihyon is often depicted sneaking into people's houses while they are away, drinking their tea, and acting as if it is their own house.[18][21] However, this depiction is not one based in folklore, but one based on hearsay and repeated in popular Yōkai media.[18][22]

Notes

- ^ a b 『広辞苑』第五版 岩波書店 2006年。

- ^ a b c d e 村上 2000, pp. 255–258

- ^ a b c d e f 志村 2011, pp. 73–75

- ^ a b 稲田篤信・田中直日編 (1992). 高田衛監修 (ed.). 鳥山石燕 画図百鬼夜行. 国書刊行会. pp. 84頁. ISBN 978-4-336-03386-4.

- ^ 稲田篤信・田中直日編 (1992). 高田衛監修 (ed.). 鳥山石燕 画図百鬼夜行. 国書刊行会. pp. 81頁. ISBN 978-4-336-03386-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g 多田 2000, p. 149

- ^ 平川林木「山陽路の妖怪」(季刊『自然と文化』1984年秋季号 日本ナショナルトラスト 44-45頁)

- ^ 村上健司他編著 (2000). 百鬼夜行解体新書. コーエー. p. 90. ISBN 978-4-87719-827-5.

- ^ 福島彬人『奇々怪々あきた伝承』無明舎 1999年 133頁 ISBN 4-89544-219-5

- ^ 秋田叢書刊行会『秋田叢書』第三巻(『雪の出羽路』雄勝郡 二) 137頁

- ^ 水木しげる『決定版日本妖怪大全 妖怪・あの世・神様』 講談社(講談社文庫) 2014年 ISBN 978-4-06-277602-8 533頁

- ^ 藤沢衛彦『妖怪画談全集 日本篇 上』中央美術社 1929年 291頁

- ^ 水木しげる『日本妖怪大全』講談社 1991年 ISBN 4-06-313210-2 330頁

- ^ 宮本幸枝・熊谷あづさ (2007). 日本の妖怪の謎と不思議. GAKKEN MOOK. 学習研究社. p. 83. ISBN 978-4-05-604760-8.

- ^ 京極夏彦 (2008). 対談集 妖怪大談義. 角川文庫. 角川書店. p. 50. ISBN 978-4-04-362005-0.

- ^ 水木しげる・京極夏彦 (1998). 水木しげるvs.京極夏彦ゲゲゲの鬼太郎解体新書. 講談社. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-4-06-330048-2.

- ^ a b Meyer 2013, p. "Nurarihyon".

- ^ a b c Foster & Kijin 2014, p. 218.

- ^ Yoda 2016, p. 64.

- ^ Zenyoji 2015, p. 230.

- ^ Mizuki 1994, p. 344-345.

- ^ Kyōgoku & Tada 2000, p. 149.

References

- Davisson, Zack (March 2015). "Back Matter: Nurarihyon". Wayward Volume One: String Theory. Image Comics. ISBN 978-1-63215-173-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Foster, Michael Dylan; Kijin, Shinonome (2014). The Book of Yōkai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520271029.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kyōgoku, Natsuhiko; Tada, Katsumi (2000). Yōkai Zukan. Kokusho Kankōkai. ISBN 978-4336041876.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Meyer, Matthew (2013). "Nurarihyon". yokai.com. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mizuki, Shigeru (1994). Zusetsu Nihon Yōkai Taizen. Kōdansha. ISBN 9784062776028.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Murakami, Kenji (2000). Yōkai Jiten. Mainichi Shinbunsha. ISBN 978-4620314280.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yoda, Hiroko (2016). Japandemonium Illustrated: The Yōkai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 9780486800356.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zenyōji, Susumu (2015). E de miru Edo no yōkai zukan. Tokyo: Kōsaidō Shuppan. ISBN 9784331519578.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

See also

External links

- Nurarihyon – The Slippery Gourd at hyakumonogatari.com (English).

- Nurarihyon from Yōkai on Mizuki Shigeru Road: Sakaiminato Sightseeing Guide Template:Ja