Baku (mythology): Difference between revisions

Undid revision 1171581715 by 189.152.75.231 (talk); reverting unhelpful additions |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''Baku'' (mythology)}} |

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''Baku'' (mythology)}} |

||

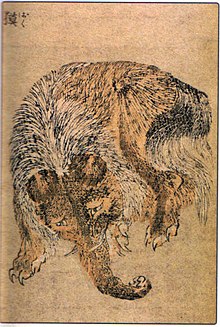

[[File:Baku by Katsushika Hokusai.jpg|thumb|right|A ''baku'', as illustrated by [[Hokusai]].]] |

[[File:Baku by Katsushika Hokusai.jpg|thumb|right|A ''baku'', as illustrated by [[Hokusai]].]] |

||

{{nihongo|'''''Baku'''''|{{linktext|獏}} {{lang|en|or}} {{linktext|貘}}}} are Japanese [[supernatural beings]] that are said to devour nightmares. According to legend, they were created by the spare pieces that were left over when the gods finished creating all other animals. They have a long history in [[Japanese folklore]] and [[Japanese art|art]], and more recently have appeared in [[manga]] and [[anime]]. |

{{nihongo|'''''Baku'''''|{{linktext|獏}} {{lang|en|or}} {{linktext|貘}}}} are Japanese [[supernatural beings]] that are said to devour nightmares. They originate from the chinese [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mo_(Chinese_zoology)|Mo]]. According to legend, they were created by the spare pieces that were left over when the gods finished creating all other animals. They have a long history in [[Japanese folklore]] and [[Japanese art|art]], and more recently have appeared in [[manga]] and [[anime]]. |

||

The Japanese term ''baku'' has two current meanings, referring to both the traditional dream-devouring creature and to the [[Malayan tapir]].<ref name="nakagawa">{{cite journal|author=Nakagawa Masako|year=1999|title=Sankai ibutsu: An early seventeenth-century Japanese illustrated manuscript|journal=Sino-Japanese Studies|volume=11|issue=24–38|pages=33–34}}</ref> In recent years, there have been changes in how the ''baku'' is depicted. |

The Japanese term ''baku'' has two current meanings, referring to both the traditional dream-devouring creature and to the [[Malayan tapir]].<ref name="nakagawa">{{cite journal|author=Nakagawa Masako|year=1999|title=Sankai ibutsu: An early seventeenth-century Japanese illustrated manuscript|journal=Sino-Japanese Studies|volume=11|issue=24–38|pages=33–34}}</ref> In recent years, there have been changes in how the ''baku'' is depicted. |

||

==History and description== |

==History and description== |

||

The traditional Japanese nightmare-devouring ''baku'' originates in [[Chinese folklore]] |

The traditional Japanese nightmare-devouring ''baku'' originates in [[Chinese folklore]] from the ''[[Mo (Chinese zoology)|mo]]'' 貘 ([[giant panda]]) and was familiar in Japan as early as the [[Muromachi period]] (14th–15th century).<ref>Hori Tadao 2005 "Cultural note on dreaming and dream study in the future: Release from nightmare and development of dream control technique," ''Sogical Rhythms'' 3 (2), 49–55.</ref> Hori Tadao has described the dream-eating abilities attributed to the traditional ''baku'' and relates them to other preventatives against nightmare such as [[amulet]]s. [[Kaii-Yōkai Denshō Database]], citing a 1957 paper, and Mizuki also describe the dream-devouring capacities of the traditional ''baku''.<ref>Mizuki, Shigeru 2004 ''Mujara 5: Tōhoku, Kyūshū-hen'' (in Japanese). Japan: Soft Garage. page 137. {{ISBN|4-86133-027-0}}.</ref> |

||

Before its adaptation to the Japanese dream-caretaker myth creature, an early 17th-century Japanese manuscript, the ''Sankai Ibutsu'' ({{nihongo2|山海異物}}), describes the ''baku'' as a shy, Chinese mythical [[chimera (mythology)|chimera]] with the trunk and tusks of an [[elephant]], the ears of a [[rhinoceros]], the tail of a [[cow]], the body of a [[bear]] and the paws of a [[tiger]], which protected against pestilence and evil, although eating nightmares was not included among its abilities.<ref name="nakagawa"/> However, in a 1791 Japanese wood-block illustration, a specifically dream-destroying ''baku'' is depicted with an elephant’s head, tusks, and trunk, with horns and tiger’s claws.<ref>Kern, Adam L. 2007 ''Manga from the Floating World: Comicbook culture and the kibyoshi of Edo Japan''. Cambridge: Harvard University Asian Center. Page 236, figure 4.26.</ref> The elephant’s head, trunk, and tusks are characteristic of ''baku'' portrayed in classical era (pre-[[Meiji period|Meiji]]) Japanese wood-block prints (see illustration) and in shrine, temple, and [[netsuke]] carvings.<ref>{{nihongo2|[http://www.sirasaki.co.jp/baku/baku.html 夢貘まくら]}}. (Accessed September 5, 2007.)</ref><ref>Richard Smart, "[http://www.japantimes.co.jp/text/fv20070216a1.html Delivering men from evil]", ''Japan Times,'' February 16, 2007. (Accessed September 8, 2007.)</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Shinto Shrine Guide - Iconography, Objects, Superstitions in Japanese Shintoism|website=Onmark Productions|url=http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/shrine-guide-2.shtml|access-date=September 8, 2007|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071016052721/http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/shrine-guide-2.shtml|archive-date=October 16, 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Baku: Monster that Eats Nightmares|website=[[Los Angeles County Museum of Art|LACMA]] Collections|url=https://collections.lacma.org/node/192199|url-status=live|archive-date=October 29, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171029091750/https://collections.lacma.org/node/192199|access-date=October 12, 2010}}</ref> |

|||

Writing in the [[Meiji period]], [[Lafcadio Hearn]] (1902) described a ''baku'' with very similar attributes that was also able to devour nightmares.<ref>Hearn, Lafcadio 1902 Kottō: ''Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs''. Macmillan. Pages 245–248. {{ISBN|4-86133-027-0}}.</ref> |

Writing in the [[Meiji period]], [[Lafcadio Hearn]] (1902) described a ''baku'' with very similar attributes that was also able to devour nightmares.<ref>Hearn, Lafcadio 1902 Kottō: ''Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs''. Macmillan. Pages 245–248. {{ISBN|4-86133-027-0}}.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 07:09, 30 January 2024

Baku (獏 or 貘) are Japanese supernatural beings that are said to devour nightmares. They originate from the chinese [[1]]. According to legend, they were created by the spare pieces that were left over when the gods finished creating all other animals. They have a long history in Japanese folklore and art, and more recently have appeared in manga and anime.

The Japanese term baku has two current meanings, referring to both the traditional dream-devouring creature and to the Malayan tapir.[1] In recent years, there have been changes in how the baku is depicted.

History and description

The traditional Japanese nightmare-devouring baku originates in Chinese folklore from the mo 貘 (giant panda) and was familiar in Japan as early as the Muromachi period (14th–15th century).[2] Hori Tadao has described the dream-eating abilities attributed to the traditional baku and relates them to other preventatives against nightmare such as amulets. Kaii-Yōkai Denshō Database, citing a 1957 paper, and Mizuki also describe the dream-devouring capacities of the traditional baku.[3]

Before its adaptation to the Japanese dream-caretaker myth creature, an early 17th-century Japanese manuscript, the Sankai Ibutsu (山海異物), describes the baku as a shy, Chinese mythical chimera with the trunk and tusks of an elephant, the ears of a rhinoceros, the tail of a cow, the body of a bear and the paws of a tiger, which protected against pestilence and evil, although eating nightmares was not included among its abilities.[1] However, in a 1791 Japanese wood-block illustration, a specifically dream-destroying baku is depicted with an elephant’s head, tusks, and trunk, with horns and tiger’s claws.[4] The elephant’s head, trunk, and tusks are characteristic of baku portrayed in classical era (pre-Meiji) Japanese wood-block prints (see illustration) and in shrine, temple, and netsuke carvings.[5][6][7][8]

Writing in the Meiji period, Lafcadio Hearn (1902) described a baku with very similar attributes that was also able to devour nightmares.[9] Legend has it that a person who wakes up from a bad dream can call out to baku. A child having a nightmare in Japan will wake up and repeat three times, "Baku-san, come eat my dream." Legends say that the baku will come into the child's room and devour the bad dream, allowing the child to go back to sleep peacefully. However, calling to the baku must be done sparingly, because if he remains hungry after eating one's nightmare, he may also devour their hopes and desires as well, leaving them to live an empty life. The baku can also be summoned for protection from bad dreams prior to falling asleep at night. In the 1910s, it was common for Japanese children to keep a baku talisman at their bedside.[10][11]

Gallery

-

Baku and Lion sculpture at the Konnoh Hachimangu Shrine, Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan

See also

References

- ^ a b Nakagawa Masako (1999). "Sankai ibutsu: An early seventeenth-century Japanese illustrated manuscript". Sino-Japanese Studies. 11 (24–38): 33–34.

- ^ Hori Tadao 2005 "Cultural note on dreaming and dream study in the future: Release from nightmare and development of dream control technique," Sogical Rhythms 3 (2), 49–55.

- ^ Mizuki, Shigeru 2004 Mujara 5: Tōhoku, Kyūshū-hen (in Japanese). Japan: Soft Garage. page 137. ISBN 4-86133-027-0.

- ^ Kern, Adam L. 2007 Manga from the Floating World: Comicbook culture and the kibyoshi of Edo Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Asian Center. Page 236, figure 4.26.

- ^ 夢貘まくら. (Accessed September 5, 2007.)

- ^ Richard Smart, "Delivering men from evil", Japan Times, February 16, 2007. (Accessed September 8, 2007.)

- ^ "Shinto Shrine Guide - Iconography, Objects, Superstitions in Japanese Shintoism". Onmark Productions. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved September 8, 2007.

- ^ "Baku: Monster that Eats Nightmares". LACMA Collections. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Hearn, Lafcadio 1902 Kottō: Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs. Macmillan. Pages 245–248. ISBN 4-86133-027-0.

- ^ M.Reese:"The Asian traditions and myths".pg.60

- ^ Hadland Davis F., "Myths and Legends of Japan" (London: G. G. Harrap, 1913)

Bibliography

- Kaii-Yōkai Denshō Database. International Research Center for Japanese Studies. Retrieved on 2007-05-12. (Summary of excerpt from Warui Yume o Mita Toki (悪い夢をみたとき, When You've Had a Bad Dream?) by Keidō Matsushita, published in volume 5 of the journal Shōnai Minzoku (庄内民俗, Shōnai Folk Customs) on June 15, 1957).

External links

- Baku – The Dream Eater at hyakumonogatari.com (English).

- Netsuke: masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains many representations of Baku